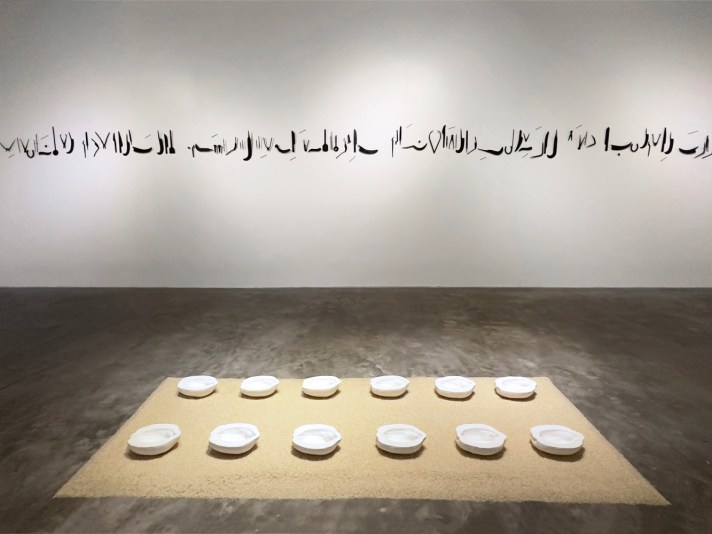

The Tomb of Begum Hazrat Mahal deals with the identity of a Muslim woman, the tragedy of war, the complete evacuation of desire and hope, and the transformation of reality into myth...I am constructing a tomb with fertility objects as a re-affirmation of resistance and courage in the lives and actions of many such women. As the spectator walks through this sombre environment, she/he becomes a participant in the violation, evacuation and reinvention.

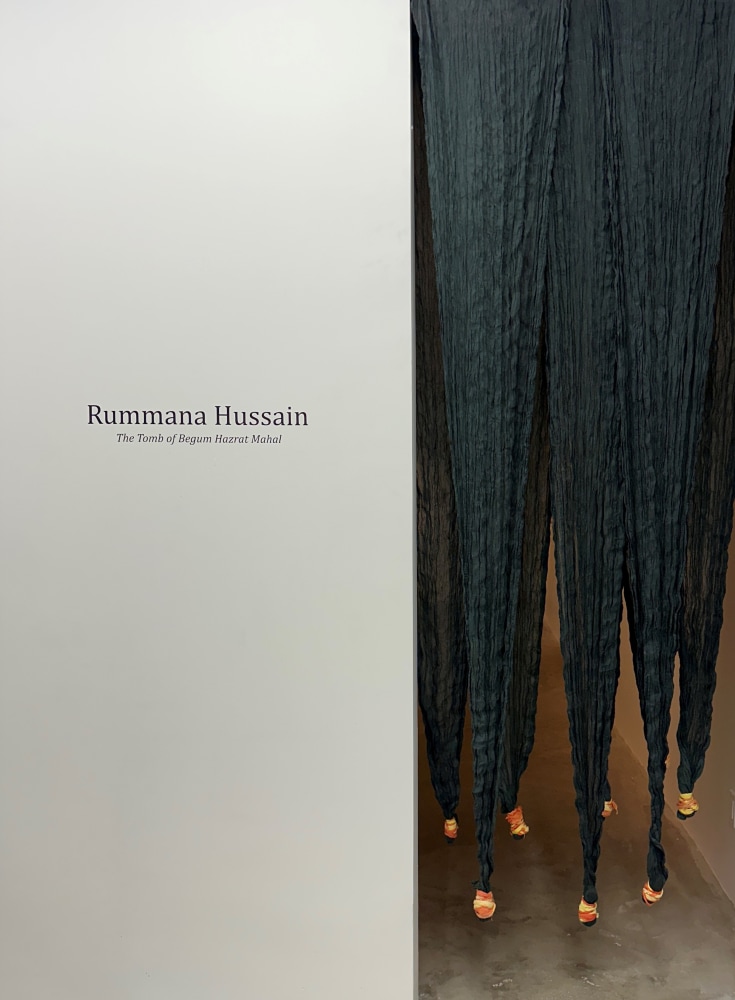

Rummana Hussain

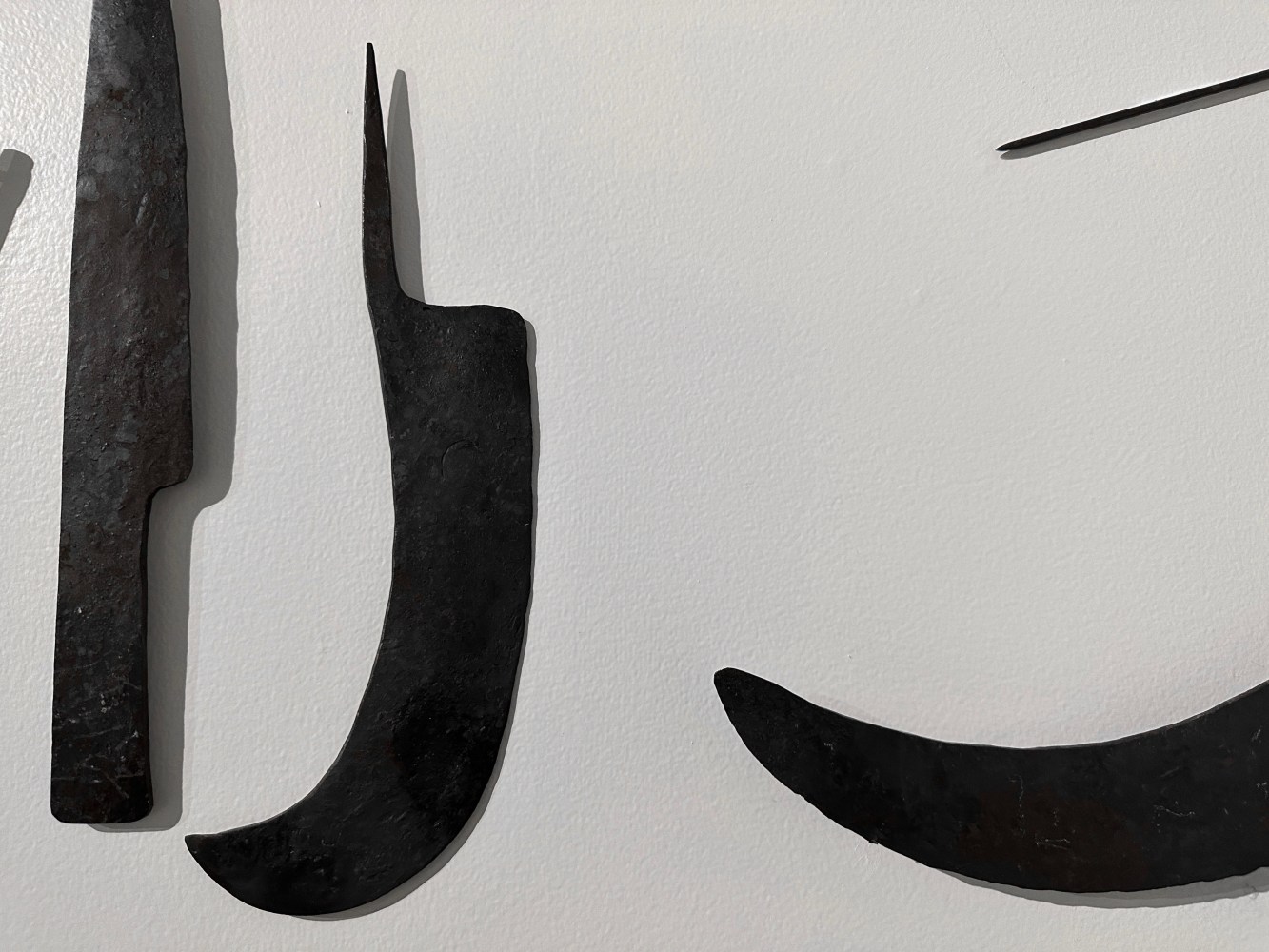

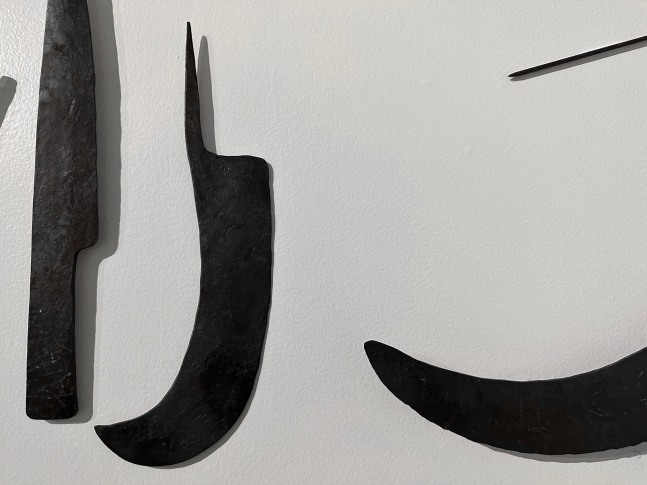

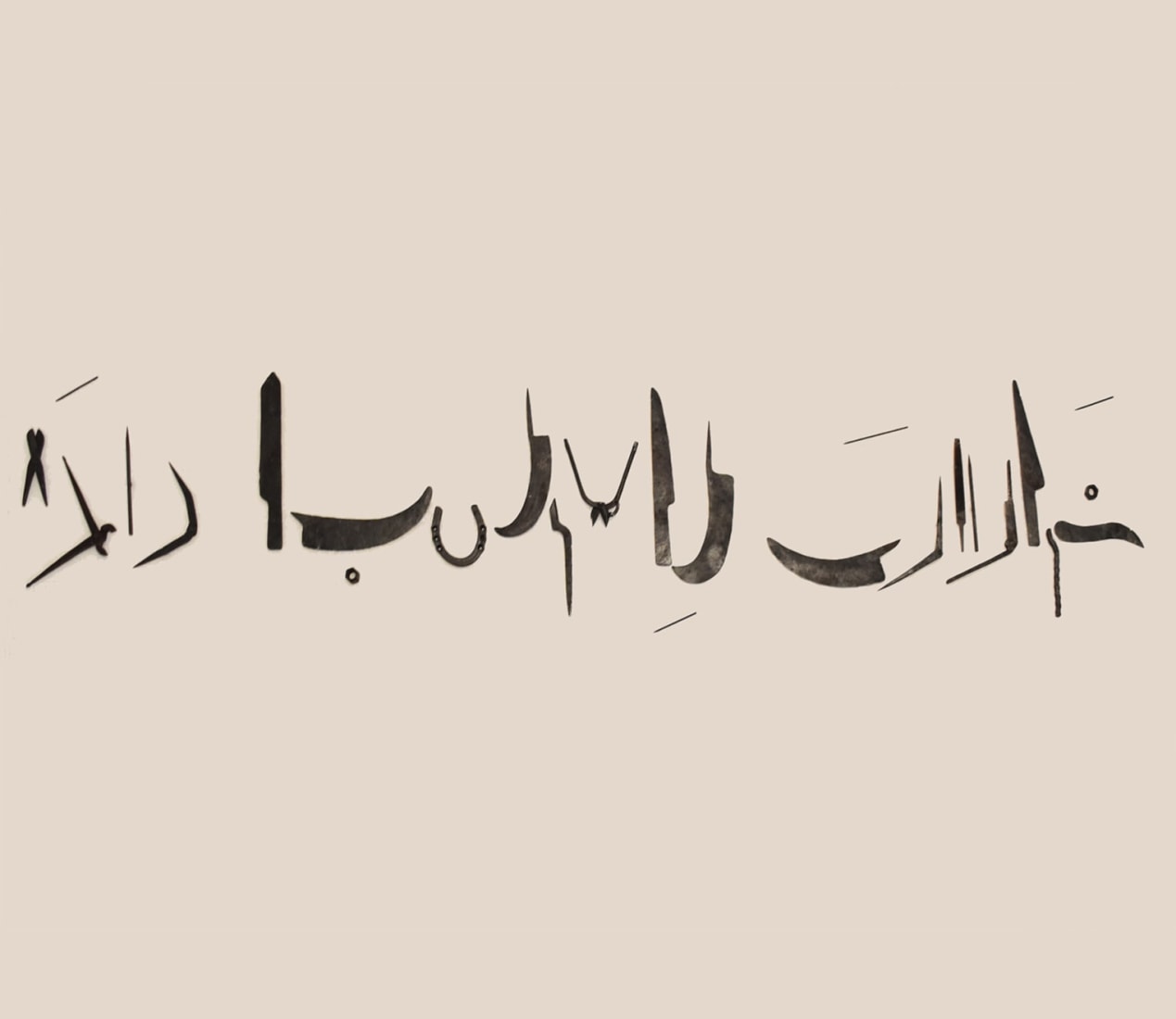

The Tomb of Begum Hazrat Mahal | Detail

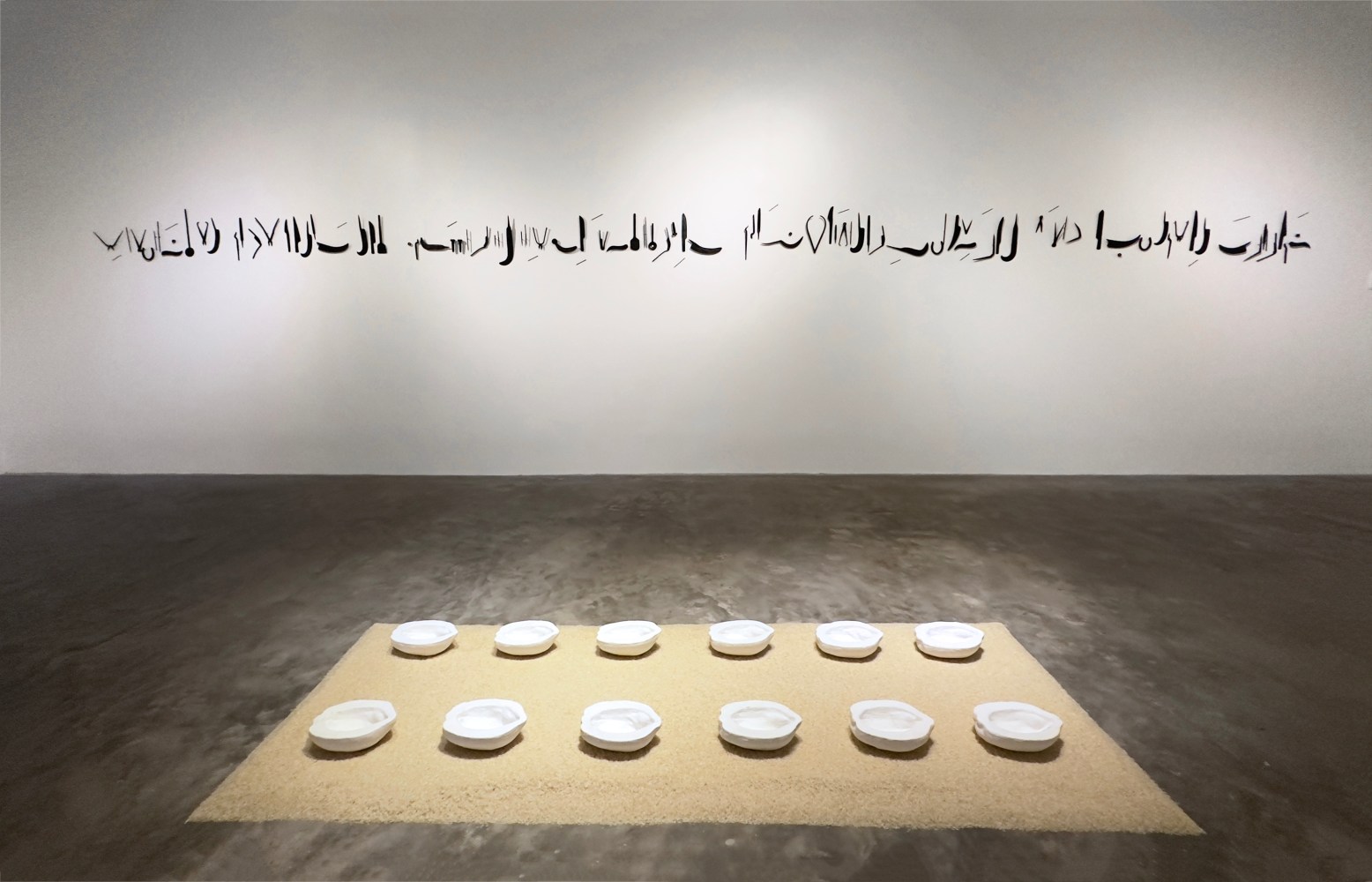

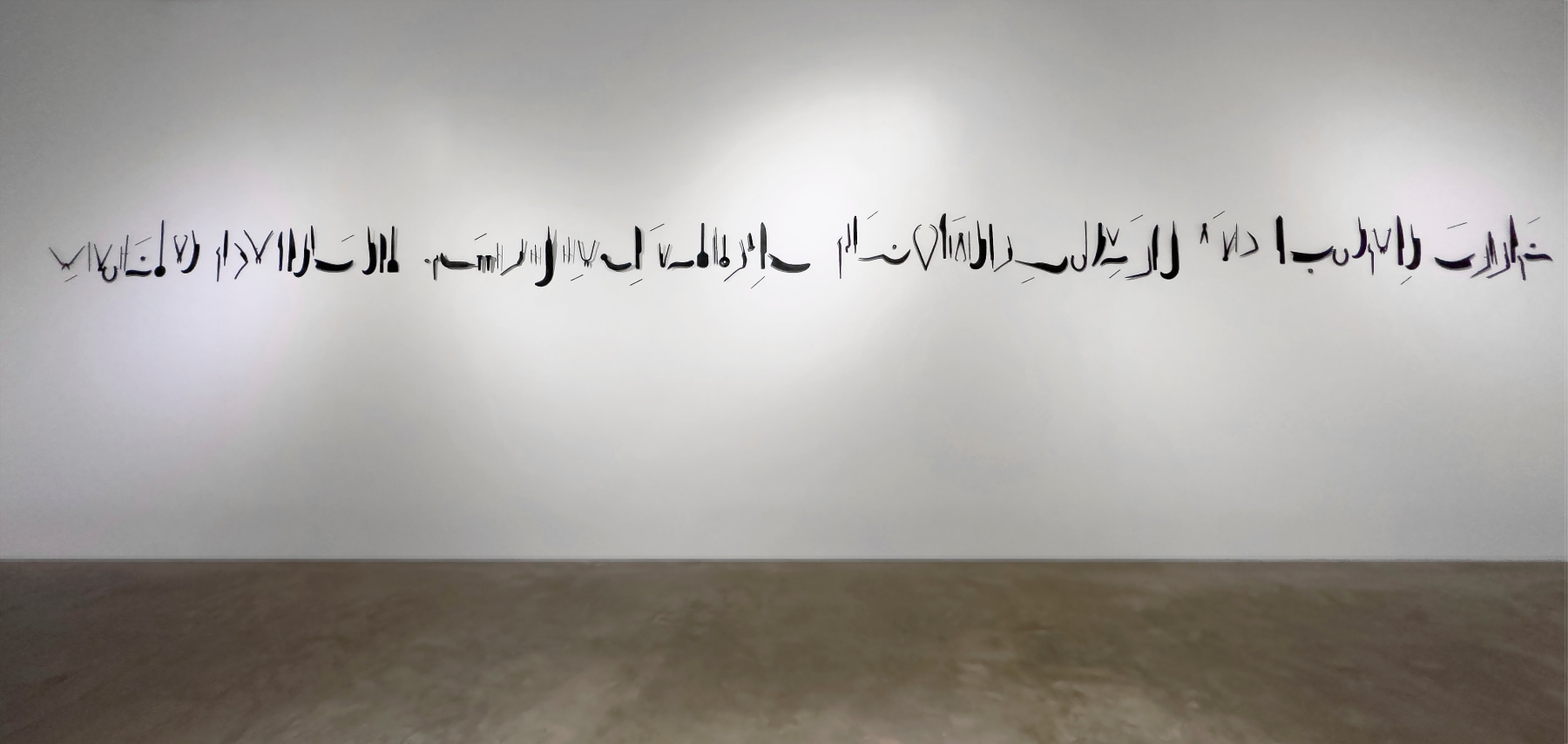

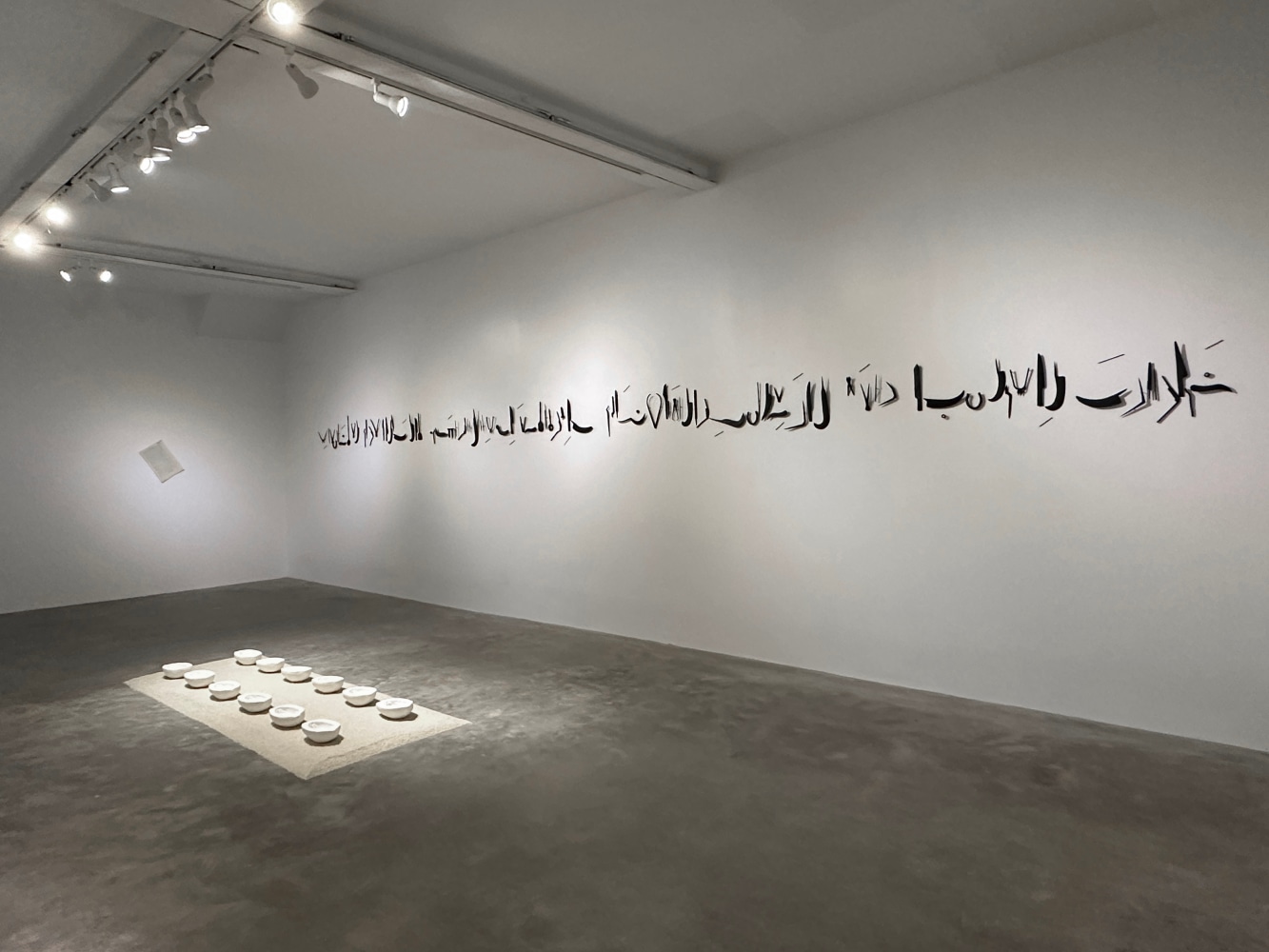

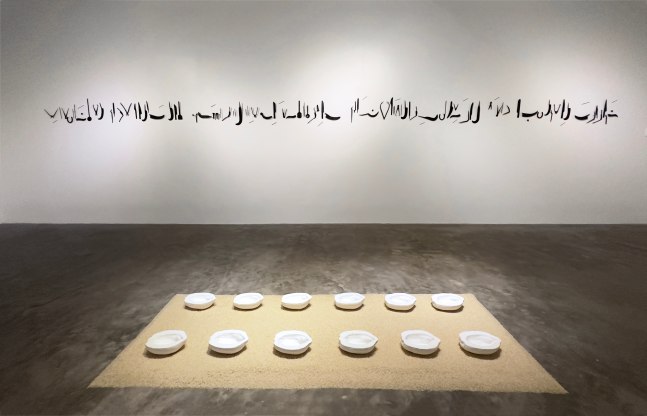

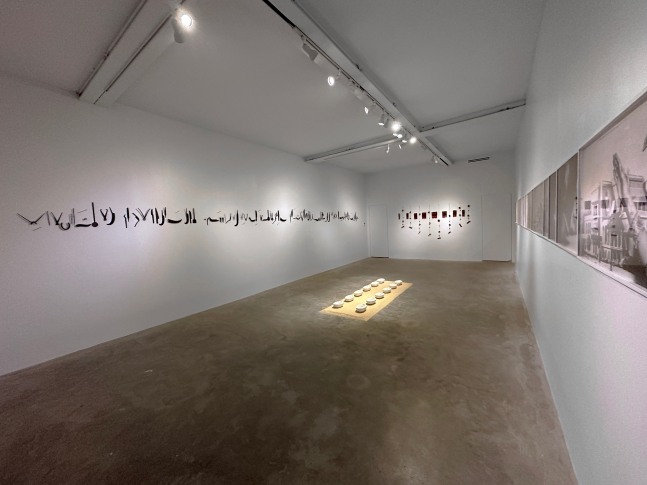

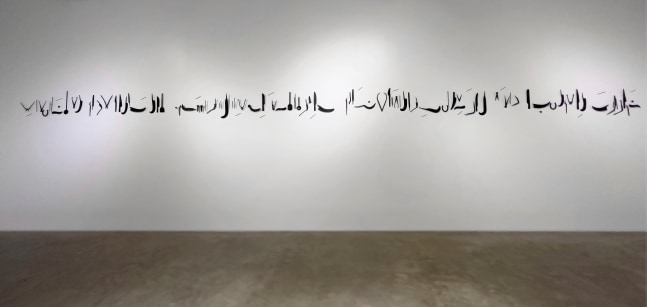

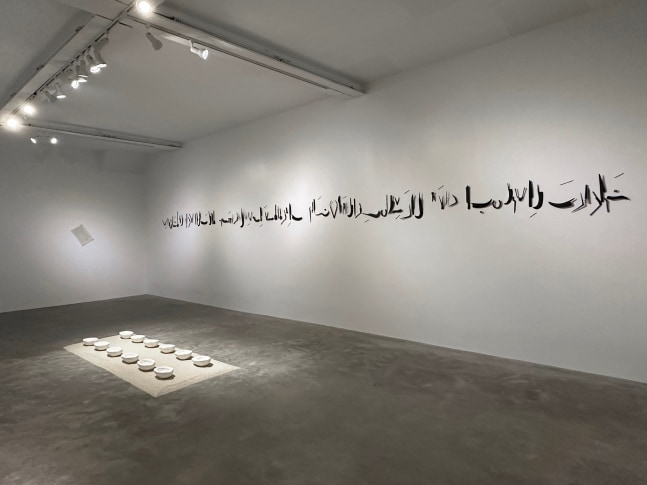

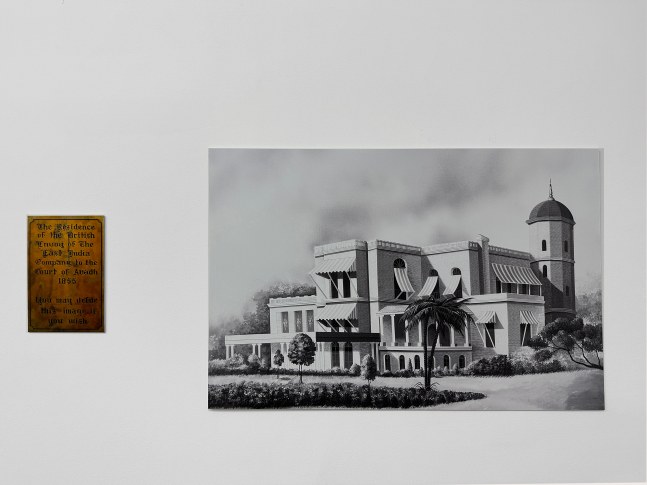

The inaugural exhibition at the Institute of Arab & Islamic Art's new location marks Indian artist Rummana Hussain’s first institutional solo presentation in the US with The Tomb of Begum Hazrat Mahal (1997), an expansive installation based work that in the artist’s true fashion, transposes identity through bodily and symbolic gestures. Tracing history, myth, and her own roots, Hussain claims Begum Hazrat Mahal, the wife of Wajid Ali Shah, as her protagonist. When her husband, the last ruler of Oudh, was ripped from power by the British and exiled to Calcutta, the Begum led an armed revolt in 1857 until ultimately defeated and driven out of Lucknow. The gallery transmutates into the walls of her tomb, a place where fragments of memory and myth collide; where Hussain provokes the female subject from a budding insurgent to an unapologetic feminist. Hussain’s world becomes less a mimetic excavation and more an altar where material fragments contend with female courage via the sacred; in Indian art critic Geeta Kapur’s words, a memory that is emphatically historical itself.

Is it the destiny of a mock-heroic figure, Rummana as begum; is it a bid for self-regeneration through exhumed narratives of past lives? Rummana’s mimicry reminds one in turn that Muslim women behind veils have fought battles in history.

Geeta Kapur

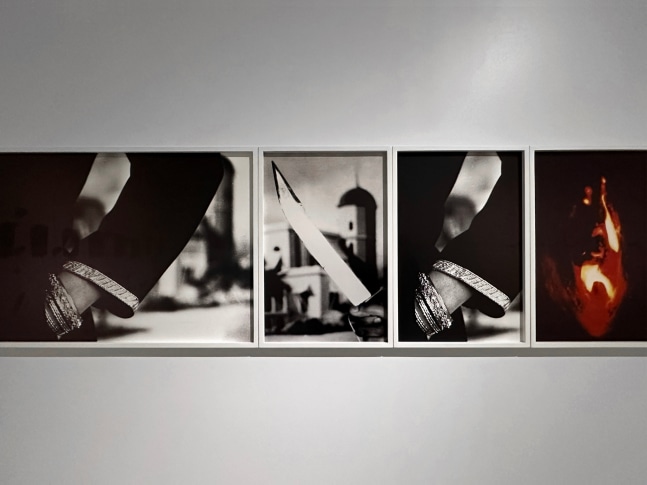

The Tomb of Begum Hazrat Mahal | Detail

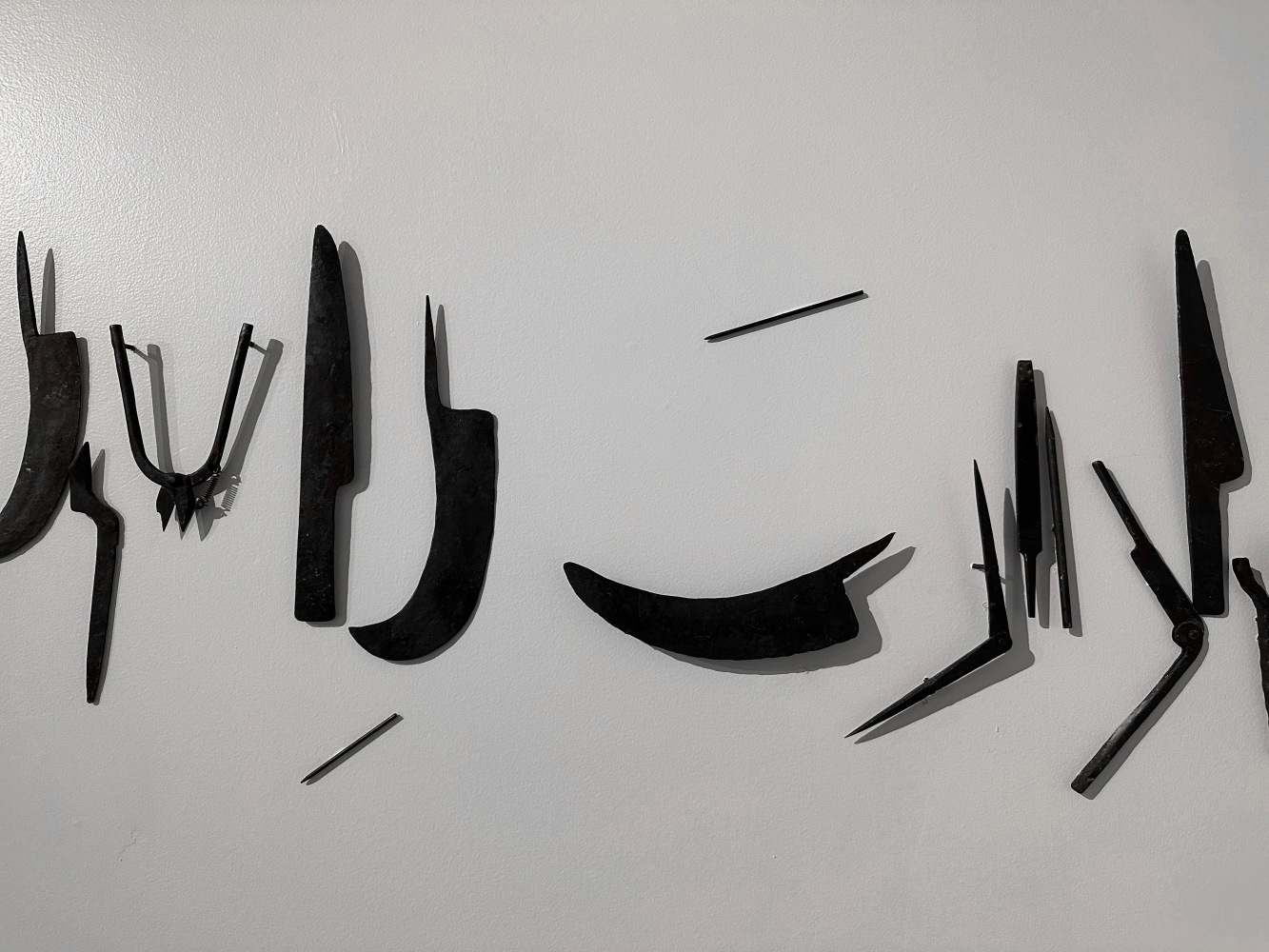

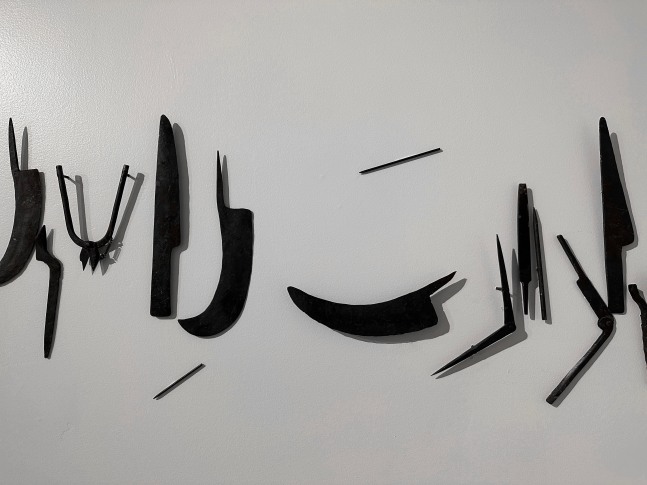

While Hussains’s legacy as a performance artist is beholden to offering her own body as a means of waiving her liberal Indian identity for the femininst cause, The Tomb of Begum Hazrat Mahal invites viewers to forge relationships with Hussain, history and testimony concurrently at various scales. The compounding effect of her various identities in India’s socio-political climate compelled Hussain to uphold her muslim identity while defending the secular, a dance that continually plays out in her work. While a series of black and white photographs of Hussain’s limbs embody the brazen gestures of the Begum to become a new living archive, rusty iron tools inscribe the facing wall with Arab- like calligraphy: a fabulated votive prayer that consciously and dialectically invokes religion. Alongside “Taveez” or lockets, dead roses and diyas tied with string, and black curtains, Hussain’s most archetypal object, the papaya halves, commands the center as an offering. An explicit visual gesture to fertility and femininity, these plaster casted, virgin-white papayas lay in rows upon uncooked rice, calling to their presence in her photographs where they appear interspersed as inflamed pyres. Amid such charged objects, we are left to wonder equally about the Begum and Rummana: whose subjectivity becomes anachronistic and whose refuses defeat.

The artist's aim was not to recover the original story in its factuality — like all histories, it is inevitably shrouded in amnesia and hearsay — nor was it an exercise in nostalgia. Instead, she both inserted herself into the fragments of it that remain (re-imagining the tale, incompletely and from her own perspective in the present) and allowed those fragments to insert themselves into her.

Jorella Andrews

Hussain has changed the way not only of expressing herself but of seeing. In doing so, she reopens issues of ancient memory and narrative as well as of recent dark and disturbing ones. It is necessary to remember these events and to keep them vivid in memory in order to be able to assess where we are today and to an extent why we are where we are.

Kamala Kapoor